We noted at the beginning of this chapter that two kinds of strings are commonly used in C++: C-strings and strings that are objects of the string class. In this section we’ll describe the first kind, which fits the theme of the chapter in that C-strings are arrays of type char. We call these strings C-strings, or C-style strings, because they were the only kind of strings available in the C language (and in the early days of C++, for that matter). They may also be called char* strings, because they can be represented as pointers to type char.

Although strings created with the string class, which we’ll examine in the next section, have superseded C-strings in many situations, C-strings are still important for a variety of reasons. First, they are used in many C library functions. Second, they will continue to appear in legacy code for years to come. And third, for students of C++, C-strings are more primitive and therefore easier to understand on a fundamental level.

C++ String Variables

As with other data types, strings can be variables or constants. We’ll look at these two entities before going on to examine more complex string operations. Here’s an example that defines a single string variable. (In this section we’ll assume the word string refers to a C-string).

It asks the user to enter a string, and places this string in the string variable. Then it displays the string. Here’s the listing for STRINGIN:

// stringin.cpp

// simple string variable

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

const int MAX = 80; //max characters in string

char str[MAX]; //string variable str

cout << “Enter a string: “;

cin >> str; //put string in str

//display string from str

cout << “You entered: “ << str << endl;

return 0;

}

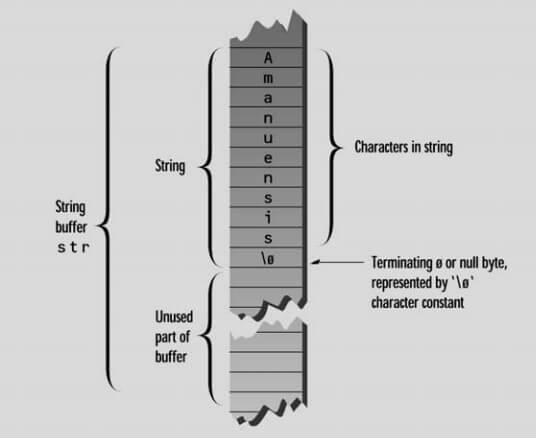

The definition of the string variable str looks like (and is) the definition of an array of type char: char str[MAX];

We use the extraction operator >> to read a string from the keyboard and place it in the string variable str. This operator knows how to deal with strings; it understands that they are arrays of characters. If the user enters the string “Amanuensis” (one employed to copy manuscripts)

Each character occupies 1 byte of memory. An important aspect of C-strings is that they must terminate with a byte containing 0. This is often represented by the character constant ‘\0’, which is a character with an ASCII value of 0. This terminating zero is called the null character. When the << operator displays the string, it displays characters until it encounters the null character.

Avoiding Buffer Overflow

The STRINGIN program invites the user to type in a string. What happens if the user enters a string that is longer than the array used to hold it? As we mentioned earlier, there is no built-in mechanism in C++ to keep a program from inserting array elements outside an array. So an overly enthusiastic typist could end up crashing the system.

However, it is possible to tell the >> operator to limit the number of characters it places in an array. The SAFETYIN program demonstrates this approach.

// safetyin.cpp

// avoids buffer overflow with cin.width

#include <iostream>

#include <iomainp> //for setw

using namespace std;

int main()

{

const int MAX = 20; //max characters in string

char str[MAX]; //string variable str

cout << “\nEnter a string: “;

cin >> setw(MAX) >> str; //put string in str,

// no more than MAX chars

cout << “You entered: “ << str << endl;

return 0;

}

This program uses the setw manipulator to specify the maximum number of characters the input buffer can accept. The user may type more characters, but the >> operator won’t insert them into the array. Actually, one character fewer than the number specified is inserted, so there is room in the buffer for the terminating null character. Thus, in SAFETYIN, a maximum of 19 characters are inserted.

String Constants

You can initialize a string to a constant value when you define it. Here’s an example, STRINIT, that does just that (with the first line of a Shakespearean sonnet):

// strinit.cpp

// initialized string

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

char str[] = “Farewell! thou art too dear for my possessing.”;

cout << str << endl;

return 0;

}

Here the string constant is written as a normal English phrase, delimited by quotes. This may seem surprising, since a string is an array of type char. In past examples you’ve seen arrays initialized to a series of values delimited by braces and separated by commas. Why isn’t str initialized the same way? In fact you could use such a sequence of character constants:

char str[] = { ‘F’, ‘a’, ‘r’, ‘e’, ‘w’, ‘e’, ‘l’, ‘l’, ‘!’,’ ‘, ‘t’, ‘h’,

and so on. Fortunately, the designers of C++ (and C) took pity on us and provided the shortcut approach shown in STRINIT. The effect is the same: The characters are placed one after the other in the array. As with all C-strings, the last character is a null (zero).

Reading Embedded Blanks

If you tried the STRINGIN program with strings that contained more than one word, you may have had an unpleasant surprise. Here’s an example:

Enter a string: Law is a bottomless pit.

You entered: Law

Where did the rest of the phrase (a quotation from the Scottish writer John Arbuthnot, 1667– 1735) go? It turns out that the extraction operator >> considers a space to be a terminating character. Thus it will read strings consisting of a single word, but anything typed after a space is thrown away.

To read text containing blanks we use another function, cin.get(). This syntax means a member function get() of the stream class of which cin is an object. The following example, BLANKSIN, shows how it’s used.

// blanksin.cpp

// reads string with embedded blanks

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

const int MAX = 80; //max characters in string

char str[MAX]; //string variable str

cout << “\nEnter a string: “;

cin.get(str, MAX); //put string in str

cout << “You entered: “ << str << endl;

return 0;

}

The first argument to cin::get() is the array address where the string being input will be placed. The second argument specifies the maximum size of the array, thus automatically avoiding buffer overrun.

Using this function, the input string is now stored in its entirety.

Enter a string: Law is a bottomless pit.

You entered: Law is a bottomless pit.

There’s a potential problem when you mix cin.get() with cin and the extraction operator (>>).

| Read More Topics |

| Program testing and debugging |

| Char array to string |

| Common Programming Error in C |